ESG and the pricing of a Near Miss

Today, let’s talk about pricing in risks for things covered by regulation.

Let’s say you’re at a refinery during turnaround (what we’d call a maintenance shutdown). One of the big tasks for the multi-week marathon is an exchanger bundle swap.

The horizontal cylinder you see on the crane above is packed with thousands of feet of densely packed steel tubing for heating up crude before it enters primary distillation. The exchanger unit is probably 30 thousand pounds.

Let’s say the area under the crane isn’t roped off. Workers are swapping valves just under the tube, now 15 feet in the air. Suddenly, the crane’s rigging snaps. The exchanger falls to the ground and lands with a sickening THUD.

Five feet away from the fallen bundle stands one of the workers. He’s in shock. He wasn’t struck by the equipment as it crashed to the ground.

But…

Nothing was stopping that worker from being just under that equipment. OSHA regulations prohibit workers from being under overhead loads and specify crane rigging and inspection. Those laws dictate requirements, but that doesn’t mean they’re followed as they should be

Pure luck saved the worker from being crushed to death that day.

The fallout from this event might involve some yelling. Maybe someone gets fired. Maybe a new crane plane for the site will be developed. But there will be no OSHA fine. No funeral. No multi-million dollar lawsuit.

This is the paradox of the Near Miss. All the ingredients for a deadly, costly, and unacceptable incident were there. It’s just that the tangible outcome wasn’t bad.

We have two options to deal with the Near miss: we can treat it like someone did die. Or, we can say, “that’s too much paperwork,” and move on from it.

But here’s the thing. We’ve got a turnaround to complete. And every extra hour of downtime is $100,000 lost. I bet you know which path usually wins.

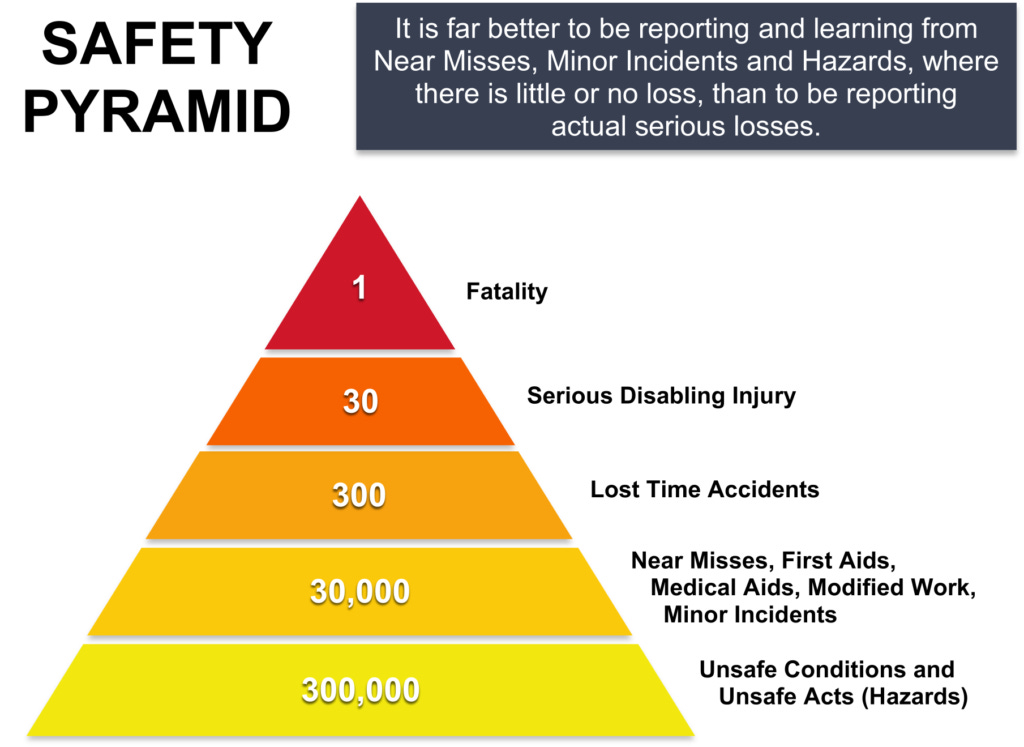

Frank Bird, one of the pioneers of process safety, developed the above graphic in the 1960s after analyzing hundreds of thousands of safety reports. The most severe sorts of accidents, death and dismemberment, will occur at rates several orders of magnitude less often than near misses.

The example I described above is a pretty extreme example of a Near Miss. But it’s a great way to think about safety. If we treat the near miss as seriously as we do the death that could’ve occurred, we would fully investigate the problem and correct it in a full and comprehensive manner.

I can assure you that today, nearly 60 years after the above graphic was produced, companies do not have records of near-miss investigations approaching an appropriate level.

Why is that? It’s because companies are bad at identifying risks that aren’t distinctly priced by markets.

On second-order risks

So much of what goes into running a successful company is not just picking a great product, marketing it, and then cutting operating costs to the extent possible. Those are the visible parts of commerce. Production. Promotion. Execution.

Any metric or investment pitch that doesn’t immediately or obviously go back to these basics is considered by some purists as a distraction from the role of a company, especially a public one.

ESG investing, in particular, has a reputation as being counter to market-based commerce. Metrics and sales pitches associated with ESG are often feel good, but ultimately meaningless buzz word soup. That is absolutely true. But the fields that encompass ESG price in a concept that is misunderstood by many market participants. That concept is what I call second order risk.

A “second order risk,” like the Near Miss scenario above, is best understood in terms of nominal financial (or first-order) risks. A first-order risk is something that is financialized and priced in, that can cost you money. This is stuff like bond issuances, insurance costs, and counterparty risk. Some first-order risks are primarily impacted by management decisions. Taking out a bond to lever up and expand to meet future demand is a calculated financialized risk, a decision made by management. But often these first order risks come to fruition for reasons entirely outside of management’s control. Think a hurricane, a global pandemic, or the economy taking a sudden nosedive.

You can price the odds of a first-order risk. Bond coupons will cost you a set amount of money on a repeatable schedule, the price of which is dictated by credit markets in general, along with industry and company-specific factors. Flood and fire insurance are market-priced goods. Importantly, however, these risks impact company earnings on an ongoing basis so they show up on every quarterly report and are considered important for good reason.

The second-order risks I think about are risks that don’t have an immediate or obvious cost. But the consequences of a second-order risk being realized is potentially catastrophic and will cost a ton of money. It’s just an indirect route to get there.

When BP didn’t complete maintenance tasks at their Texas City refinery for years, despite repeatedly being flagged in audits, they acted like they were taking a rational financial risk. Poor maintenance means a higher chance of future outages and reduces the viable lifespan of the equipment. But those are easily represented as accounting costs; dollars and cents.

In 2005, this refinery had a catastrophic explosion, tied primarily to poor maintenance and upkeep. Fifteen people died as a result. This incident cost the company untold billions in fines, repairs, and lawsuits. It also did significant damage to BPs reputation and brand.

In retrospect, it’s easy (and correct) to say BP obviously should’ve done maintenance as suggested in internal documents. But these sorts of risk assessments for second-order events are complex; as a result, companies are generally quite bad at identifying them. This is because there is no market to price these costs.

It’s no wonder that so many second-order risks are covered extensively by regulation. Strict adherence to OSHA and EPA process safety standards would’ve likely corrected the problem at Texas City.

ESG Tries to (And Sometimes Succeeds at) Pricing Other Risks

If we stop and think about the components of ESG; Environmental, Social, and Governance, not as fluffy, feel-good things, but rather from a risk framework, it starts to make a bit more sense.

Environmental requirements at times bring in Greenwashing (Which we hate here at ESG Hound), but more often than not, the “Environmental” sections of ESG reporting focus on the brass tacks of, well, complying with the law. Do you think that VW, after the multi-billion dollar Dieselgate scandal and criminal conviction of several executives, might have had problems with their internal Environmental programs as a whole? I suspect they did. Wouldn’t it be nice if investors could visualize environmental reporting and permitting compliance, using the data as a soft proxy for perhaps other Second-order risks that lay beneath the surface?

Social requirements under ESG are a bit softer than Environmental ones, but data has shown repeatedly that companies with diverse management and open dialogues with employees are less likely to have to deal with EEOC claims and harassment or discrimination suits. These sorts of issues can damage a brand (LOOKING AT YOU ELON MUSK) and are expensive. That’s a real cost and a financial risk.

Governance reporting requirements and standards have been fairly normalized over the past few decades following the spate of fraudulent corporate blowups in the early 2000s. Because having good Governance has been mostly normalized and accepted by Wall Street as a given requirement over the past few decades, “G” is easily the least controversial letter in the acronym.

So: for all the ESG haters out there: are you still sure you don’t want to take a look at an oil company’s ESG report before you invest next time? You just might find a new way to identify costs that aren’t being considered by the market. That sounds like pure investing alpha to me.