REC Silicon (REISI.OL), the IRA, and the Benefits of being listed in the US

Let's go Brandon! Make those Chips!

As a natural cynic, putting out a post about a company that is positive, upbeat, and optimistic that a company’s management *isn’t* overpromising on the future feels deeply unnatural. But that’s what I’m doing today. It’s not exactly a first for me, but it certainly goes against the thematic push of this publication I’ve been shepherding for two and a half years now.

Green companies have been a hotbed for dodgy business plans, absurd unit economics and a playground for grifters for a long time. Long-time followers of mine know that, while I appreciate much of what the ESG framework provides in terms of investor disclosure and positive synergies between Market forces and responsible stewardship, the potential cash grab of promoting stocks based on non-economic considerations serves as a big flashing sign to bad actors that says “SUCKERS AHEAD, DO CRIME HERE!”

Perhaps no single asset symbolizes this pitfall more than the solar panel. We get a lot of energy from the sun. The irradiance upon a few thousand square miles of equatorial land is enough energy to theoretically power all human society worldwide. And it’s not like the mechanism to capture this energy is particularly complex. A photon strikes a photochemical cell, displacing an electron from a (typically silicon) layer from one end of the cell. This “freed” electron can then be routed through a conductive metal to the second (also typically silicon) layer of the cell. That flow of electrons is electrical work (or power).

I’m not going to belabor the intricacies of solar panels because it is both well above my pay grade and (almost) entirely incidental to the crux of this post. The point is that we need lots of silicon, in the form of polysilicon, to make solar panels.

Ironically, what spurred my initial interest in the “ESG” case as both a promise for a better future and the potentially grift-tastic downsides involved Solar panels but not silicon. In 2010, well after it was clear that Fremont, California-based solar panel manufacturer Solyndra was a Bad Business™️, the Obama administration rubber-stamped a half-billion-dollar Department of Energy loan. Fifteen months later, the company would declare bankruptcy.

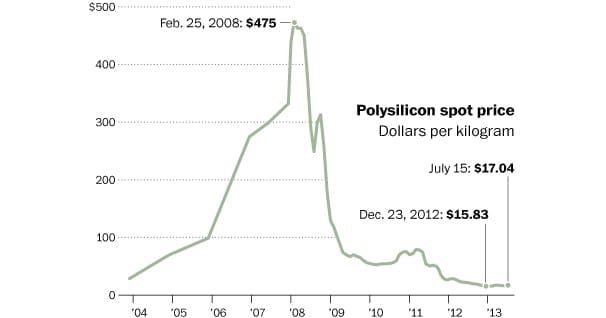

Between 2009 and 2011, polysilicon prices fell 90%. Solyndra’s pitch was that their silicon-free solar tube technology would be economically viable because of their use of copper-indium-gallium-diselenide (CIGS) film instead of polysilicon. But everyone with a functioning brain, including the US Department of Energy as early as 2008, could see that polysilicon prices were headed towards a dramatic collapse as China spun up factories to produce the stuff.

So tl;dr the US government bought some BoredApe Slurp Juice at the post-Beeple Sotheby’s NFT peak. It happens.

Solyndra wasn’t the only loser in the early 2010’s blowout. The REC Corporation, a Norweigan-based manufacturer of Silicon and Silane Gas, bought a Union Carbide Silicon plant in Lake Moses, Washington in 2002 via a joint venture with Komatsu. They added capacity in 2006, committed more capital to another polysilicon production train in 2007 and started up the final process unit in 2010.

The company also finalized the purchase of a Silane and Polysilicon plant in 2009 in Butte Montana. These were not incredible transactions, in retrospect:

Adding insult to injury, the company closed down its Washington facility in 2019, almost at the exact bottom.

The current iteration of the American asset portion of the company (following a split in 2013), trades on in Oslo. Sporting a market capitalization of 7.23 Billion Krone ($719 million), the fundamentals look horrific on the surface:

And the company trades like a distressed asset.

But the stock market is forward-looking, right? So what’s there to get excited about as an investor? Well, if we’re listening to company management, they’d tell you the following:

The Lake Moses, Washington Plant is set to re-start operations in late 2023

The facility will be able to produce at a rate of 20 million/per annum tons of solar grade silicon by the end of 2024

Silicon prices should stabilize in the $20 range which will lead to significant EBITDA growth

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) will be a significant tailwind as well

So, we have questions to ask ourselves:

Is the market not adequately pricing in these potential near term upsides? If so, Why not?

Do we trust management’s projections about the facility restart? How can we confirm this?

How should we value the company going forward?

Let’s dig in!

Indexing, Herding, and Listing

Let’s take a bucket of companies in the broad solar sector and look at their performance since the 2019 lows in polysilicon prices:

REC Silicon (RECSI) - US-only Manufacturer of Polysilicon, listed on Norway’s stock exchange

SunRun (SUN) - US Listed installer of solar panels.

Xinyi Solar (968.HK) - Hong Kong listed manufacturer of photovoltaic glass

SolarEdge (SEDG) - Consumer and Business facing distributor of solar and adjacent technologies (Battery backup, inverters, chargers) with proprietary tech

The selection criteria for my three comps aren’t entirely arbitrary. These three companies are huge portions of the Invesco Solar ETF TAN 0.00%↑ (SEDG 9.1%, Xinyi 6.1%, SUN 4.6%). RECSI isn’t in this fund. Nor is it in the iShares Global Clean Energy ETF ICLN 0.00%↑ .

The Top ten holdings of TAN look like this on a valuation basis:

This is a blend of commodity producers (0968.HK, 3800.HK), consumer finance companies cosplaying as green tech companies (RUN), Panel and Inverter producers using proprietary processes (FSLR, ENPH) and consumer-facing brands that blend software, marketing and hardware sales (SEDG, and ENPH).

RECSI has had a nice runup since just before the passage of the IRA by congress (+60%), but as the stock chart above shows, it’s mostly getting herded with generic solar names. Not entirely unexpected since the stock is not listed on US exchanges and has next to no analyst coverage.

RECSI - The catalyst that isn’t getting priced in

Last year, the company told investors they were re-starting their Moses Lake, Washington facility at the end of 2023. A quick look at EBITDA vs spot polysilicon prices shows why (1) the facility was shuttered in the first place and (2) why they may want to be eager to re-start production.

EBITDA is not my favorite metric for evaluating capital-intensive manufacturing1. A nominally positive 2016 through 2018 on the EBITDA front underscored just how much cash the company was incinerating:

But we’re looking at this as an event-driven play. If the company can get back to production levels seen the last time polysilicon was trading at the $15-25/kg price and a 10x EV/EBITDA valuation, things start to look pretty nice. More on this in part next week.

Nothing in Permitting Documentation Indicates they can’t re-start

The RECSI “can they build it?” story starkly contrasts my most recent equity analysis (on ENVX). ENVX has a brand new, unproven manufacturing process and are relying on a Malaysian microcap to get financing to get the ball rolling.

RECSI has a plant, with proven production capabilities, already constructed in the US. The technology isn’t new or exciting; it’s just that the plant isn’t operating right now and the company will have to get operations ramped up again. They claim startup will occur at the end of the year and that operations will be back to normal by 2025.

So I did what I usually do: took a look at permitting documents for the company. Here’s a summary of what I found.

The company’s Moses Lake facility in Washington, as currently designed, was permitted in 2009 and closed in 2019

Records requests from (the painfully slow) Washington State open records law show that in early 2022, the company submitted an initial request to restart production and make minor modification to a few buildings

Full approval was granted in May 2023 to restart production

You can find the main permitting document I acquired here.

I approached this facility’s documentation review with the normal critical approach I use for looking at permitting documents:

In other words, I approached it as if I was looking at the company as a potential short. This involved looking at mass balances, permit limits, and other restrictions on a permit. I found that the management’s representation of the facility matched the documents. This isn’t an unusual occurrence, as most of the time, there’s not much drama or excitement when doing these types of reviews.

One thing I was concerned about going in was that the company had possibly lapsed in reporting or paying fees on their Existing Title V major source air permit. That alone could cost the company months or years of excruciating permitting. The company filed all reports as required and kept the permit’s rolling 5 year renewal process chugging along, even as the facility was temporarily shuttered.

The permit limits themselves are mass balance based, and as a result, a material input limit is right there in the permit:

We can use the annual metallurgical grade silicon (MGS) limit of 62.5 million pounds per year as a basis for rough financial projections.

This facility will, once restarted, be one of the only polysilicon (PS) production facilities in the US. We can assume a 90-95% total yield of PS from MGS. Some of the MGS will end up as Silane gas, but since there is carry-through in the supply chain as well as Inflation Reduction Act credits, we will treat all production as solid solar-grade polysilicon. This is the conservative approach.

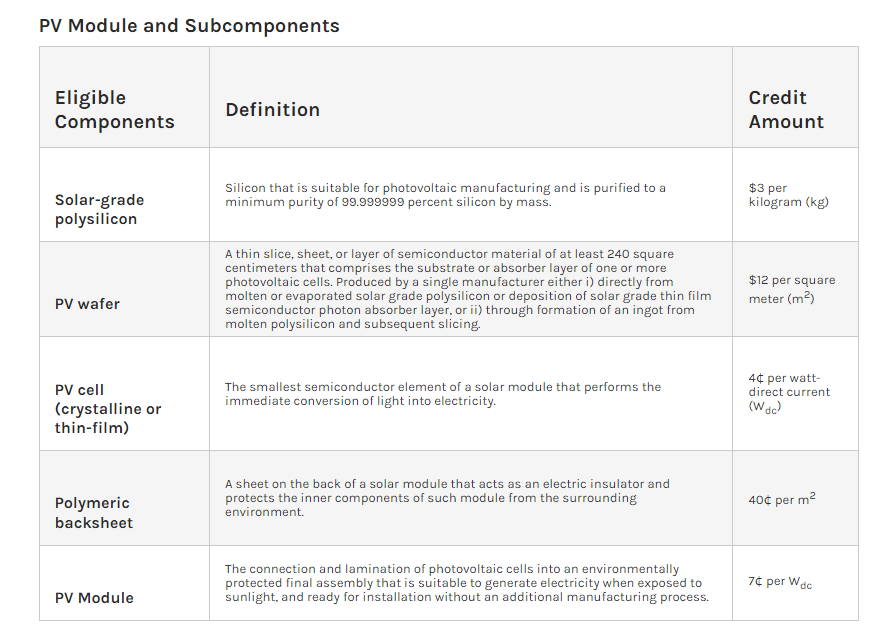

At 90% yield, we come up with 25 million kilograms of end product. The IRA has a flat credit of $3/kg for 100% American-produced material:

All else equal, and at full production, we can add $75 million in annual profits versus their foreign competitors. The company is also in the process of partnering with Korean conglomerate Hanwha, who is in the process of slowly dominating US solar cell production. Hanwha also happens to be a major investor in REC.

I am aiming for a part two on this company next week, where I will go into the financials further but I really want to stop there and focus on the logistics of restarting a large production facility before signing off.

These types of projects require massive capital to rehabilitate the facilities themselves. Agencies must be coordinated with well in advance. REC management didn’t tell investors as soon as it was clear in 2021 that things were getting better that they’d be up and running in a few months. They instead sat down with experts internally and discussed the maintenance, capital construction, and logistic requirements of pulling off restarting a complex multi-billion dollar facility.

REC management has regularly kept investors abreast with developments as they occur, and to my outsider’s eye, has given realistic timelines for completing this re-start project.

I am long RECSI common shares and think it has significant upside as one of the only pure-play US silicone producers.

Disclosure: This report is the sole work of myself. I was not paid or commissioned to write it. However, as an independent contractor, I currently provide research and advisory services to financial firms, funds, startups and companies, public and private alike. None of the above should be considered investing advice.

8/2/22 Editors note: Removed EBITDA assumptions that included incorrect calculations (combined companies + Forex issue).

EBITDA can be useful for intraindustry comps, and that’s one measure that analysts use in the space (EV/EBITDA), so we’ll stick with it for this piece