Lest I be accused of publishing clickbait, I’m 100% serious about the title of this post.

People have asked me over the years, from individual clients to readers of this fine publication, “Where did you find this incredible information?”

Despite my reputation as “The guy who yells about SpaceX,” the work that has engaged some of my most valuable connections since starting ESG Hound nearly two years ago was due to things like the work I did on Gevo ( GEVO 0.00%↑ ), the “revolutionary” biofuels company with a heavily greenwashed story and fake narrative about negative carbon footprint jet fuel from corn.

Gevo, despite the green stimulus Inflation Reduction Act and several years of high oil prices, is down 80% from when I first wrote about it, well on its way to going bankrupt.

I proved that their story was nonsense not by coming upon a secret document or a whistleblower but by combing through government databases, public records requests, academic research, and doing some basic math.

But the most powerful tool in my arsenal is a free database, funded by the US government, with highly specific search parameters, an embedded map graphical user interface (GUI), and a powerful API that I can link into Excel spreadsheets.

What is this tool? Why, It’s EPA’s ECHO database.

Please like and share this post. If you find value in this kind of work, consider upgrading to the paid tier.

ECHO: The best research tool for looking behind the corporate veil of industrial America

Prior to 1995, information submitted by companies to EPA that was intended for public review was contained in a disconnected mess of databases, digital and physical alike.

The Toxic Release Inventory system, a part of the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA) included reporting requirements for facilities subject to Risk Management Plan (RMP) in the mid 1990s. RMP is a public disclosure system for facilities that pose a risk to surrounding communities in the event of an accident, explosion or release. Think Refineries, Chemical Plants and places that use large quantities of other toxic chemicals, such as Ammonia.

EPA rolled out the Facility Registration System (FRS) to tie disclosure requirements for individual facilities to a central, linked identifier. From there, all disconnected databases were eventually rolled into systems like EPA ECHO.

The amount of useful, interesting data contained in ECHO is astounding. But instead of describing what is in this tool, let me walk you through how I use it to find interesting research.

Let’s say I want to look at the Aluminum Secondary Smelting business. This is defined by the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) as follows:

This U.S. industry comprises establishments primarily engaged in (1) flat rolling or continuous casting sheet, plate, foil and welded tube from purchased aluminum and/or (2) recovering aluminum from scrap and flat rolling or continuous casting sheet, plate, foil, and welded tube in integrated mills.

Maybe I want to know where these facilities are located. How many are in each State? Where are they concentrated? What are the surrounding demographics of these plants? Maybe I want to research the Greenhouse Emissions of the Industry as a whole.

This kind of research sounds like something that you’d pay a boutique researcher out the nose for. I have done consulting work for research exactly like this. And you can too! Let’s walk through an exercise with one of these prompts.

How I use ECHO (The Basics)

On a very basic level, ECHO has some powerful aggregating features such as “Listing all the Facilities who operate under NAICS Code 331314 - Secondary Smelting and Alloying of Aluminum.

Under advanced search from the ECHO website, I can do a simple search for this SIC code. ECHO spits out a data table and a map that looks like this.

165 Facilities is a lot. Not every company in the country is listed in FRS, since plenty of facilities have de minimus or no environmental requirements reportable to EPA. Even some light manufacturing facilities will not go above reporting thresholds and could remain undetected. This is where a bit of domain expertise comes in. I know that every since every single one of these companies will have an FRS registration because they are all subject to Area source requirements (no de minimus level of emissions) under NESHAP of the Clean Air Act (40 CFR Part 63 Subpart XXXXXX). So I don’t particularly worry about not catching every facility in the nation.

I can even download a quick data table of the results that looks like this:

With a little more work (including using EPA’s quite powerful API) I can even pull individual air emissions of pollutants, such as hydrochloric acid for all 165 facilities. But that’s perhaps a topic for a later date.

Some of the top-level filtering can be quite powerful, such as searching for facilities that are Major Sources under the Clean Air Act or ones that have major violations in the past 3 years.

There are also super interesting demographic screens. For example, I pulled data from the linked Environmental Justice database on Major Aluminum manufacturers, showing what percentage of the population within three miles of the facilities are considered “Low income.” The average is 37% across industry, by the way.

Aside from data about Environmental Justice and compliance data, environmental data can be a powerful surrogate for production. Alcoa, the Aluminum giant, has facilities across the US.

Direct outputs of individual facilities are often mysterious in public filings. This includes SEC filings for publicly traded companies. EPA doesn’t track tons of bauxite production, but emissions and discharges to the environment are often powerful surrogates for this data.

Knowing a few things about the underlying process comes in handy here. We know that as an energy-heavy process, industrial furnaces and smelters are used to produce the final metal products. Therefore, in places where annual CO2 emissions are required to be reported, the annual emissions from products of combustion are an amazing surrogate for things like metal production.

Alcoa’s very large Newburgh, IN facility is required to report CO2 emissions annually, along with other emissions. They can be found linked in ECHO in the TRI emissions report:

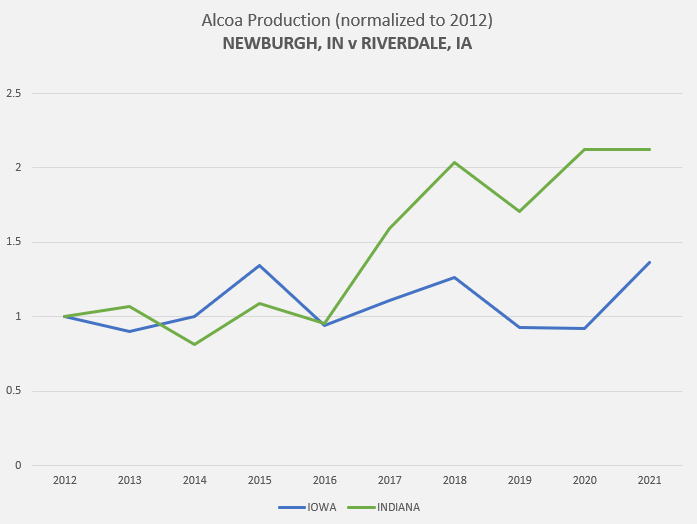

Alcoa’s much smaller Riverdale, IA facility does not have to report GHG emissions. But they do have to report Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) emissions every year. With a quick look at permitting documents, I can see that HCl emissions are a great surrogate for bauxite production as emissions are a function of throughput and a set mass of HCl is consumed per ton of final product.

Using the HCl emissions as a surrogate and with each facility indexed to 2012, we can generate the following chart:

This chart shows a couple of things. First, the Iowa facility, having not gone through a major expansion in a few decades, is very price sensitive. Production picked up again in 2021 as commodity prices soared.

The Indiana facility had a major capital improvement expansion completed in 2017. Because of location and economies of scale, production tends to run at close to 100% regardless of market conditions. We can visualize these dynamics at play just using EPA data!

This kind of research is incredible for publicly traded companies for people who want a closer look at the inner workings of an organization that they may not readily disclose to investors. But for research into private firms, it’s simply unbeatable.

More to come!

I really enjoy writing about this kind of stuff and I hope you find value in it. This truly is the tip of the iceberg in terms of doing research using public data sets. We’ll cover more in later issues for my paid subscribers, but in the meantime, if there’s a request for some “industrial espionage” I can take a look at in the future and show you how I work, please comment below.